Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

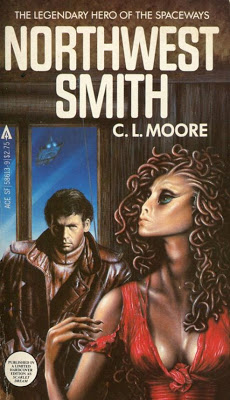

Today we’re looking at “Shambleau,” C. L. Moore’s debut story first published in the November 1933 issue of Weird Tales.

Spoilers ahead (for a couple other Moore stories as well as this one).

“Somewhere beyond the Egyptians, in that dimness out of which come echoes of half-mythical names—Atlantis, Mu—somewhere back of history’s first beginnings there must have been an age when mankind, like us today, built cities of steel to house its star-roving ships and knew the names of the planets in their own native tongues—heard Venus’s people call their wet world “Sha-ardol” in that soft, sweet, slurring speech and mimicked Mars’ guttural ‘Lakkdiz’ from the harsh tongues of Mars’ dryland dwellers. You may be sure of it.”

Summary

Prologuery—Man has conquered Space before. That is, men of pre-Egyptian civilizations like those we call Atlantis or Mu. They explored Venus, called Sha-ardol by its natives, and Mars, called Lakkdiz. Humanity has forgotten them except in myths of beings like the Medusa. Pure invention or echo of memory from primordial ancestors? Let’s ask….

Northwest Smith, space pirate with a heart of somewhat adulterated gold and a heat-pistol. He’s right at home in one of Earth’s wild Martian outposts, where he’s setting up a deal we’d better not inquire about. His equally nefarious Venusian partner Yarol will join him in a few days. Prowling the slag-red pavements, he encounters a mob pursuing a scarlet-clad, turbaned girl. She dodges into Smith’s alley and collapses at his feet. Shambleau! Shambleau! shouts the mob, and their leader tells Smith that they must kill the girl because she’s just that, a Shambleau.

Smith doesn’t know what a Shambleau is, but he tells the crowd the girl is his. Strangely this turns their rage into contempt and disgust at Smith himself, and they retreat. Baffled, Smith studies his new “acquisition,” a brown-skinned alien, green-eyed and slit-pupiled, but with the sweetly curved body of a woman. She speaks little of his language but explains she’s Shambleau, from a country long ago and far away. For all her dishevelment, her poise is queenly.

Smith takes her to his lodging house, where she can stay safely until he leaves Mars. When he returns from business and drinking that night, she’s sitting in the dark, which she says is the same to her as light. Her smile, which would be provocative in a woman, strikes Smith as somehow pitiful and horrible, but excitement still stirs in him. They embrace. He gazes into her feline green eyes. Something beneath their surface makes him shove her away. She falls. Her turban slips—she’s not bald, after all, because a red lock tumbles down on her cheek. It seems to squirm before she pushes it back, but hey, Smith’s pretty drunk.

He goes to bed alone, while the girl curls up on the floor. He dreams that something soft and wet coils around his neck, caressing him to a soul-deep and dreadful ecstasy, hateful but foully sweet. The girl’s still there when he wakes. He leaves her on more vague business, returns with various foodstuffs. She wants none of them—she eats something better. Thinking of her kitten-sharp teeth, Smith says, what, blood? No, she’s no vampire, she’s Shambleau! Smith is again attracted to her, again repulsed by something in her eyes.

Late that night he wakes to see the girl unwinding her turban. Instead of hair, she releases a mass of scarlet squirming—worms?—that grow as he watches. Shock freezes Smith; though he dreads the turn of her head and glance of her eyes, he can’t avoid it. Her eyes promise nameless but not unpleasant things. She rises, her—hair—falling like a wet, writhing cloak around her, yet she’s soul-shakingly desirable, and Smith stumbles into her arms and wormy tresses. The foul yet irresistible ecstasy of his dream, multiplied a thousandfold, drives off initial nausea. Medusa has turned him to helpless marble; though he knows the soul should not be touched, he can only yield to devouring rapture.

Three days later, partner Yarol arrives at the lodging, to find nothing but a mound of living entrails. At his calls Smith emerges, slimy, gray, dead-alive. He tells Yarol to leave him alone. The mound rises—its tendrils part to reveal a cat-eyed girl. Yarol wrenches Smith free but nearly succumbs himself to the tendrils’ caresses. The sight of a cracked mirror wakes his memory of something he read long ago, and he uses the mirror’s reflection to shoot the monster without looking directly at it.

Smith wakes to Yarol pouring reviving liquor down his throat. Yarol tells him he was nearly the victim of the Shambleau, a vampiric creature from who-knows-where, although Yarol heard legends of them on Venus. They must have existed on Earth, too. Think of the legend of the gorgons. That’s what saved them both, Yarol remembering how Perseus slew Medusa by looking only at her reflection.

Smith mutters of his terror and pleasure in the Shambleau’s embrace. He became part of the monster, sharing its memory and emotions and hungers. He visited unbelievable places—if only he could remember!

Thank your God you don’t, Yarol says. When Smith wonders whether one might find another Shambleau somewhere, Yarol makes him promise that if he ever does, he’ll kill it at once. Smith hesitates long, eyes blank with memories both sweet and horrible. Finally, he vows that he’ll try. And his voice wavers.

What’s Cyclopean: Northwest keeps being “unaccountably” disturbed by Shambleau. “I do not think that word means what you think it means.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Having the lynch mob be right is always a questionable choice. But both Northwest and Shambleau are casually described as brown-skinned—even if that’s meant to be a rugged tan, it sets a refreshing default.

Mythos Making: There are races older than man… and this is terrifying.

Libronomicon: Northwest doesn’t seem like much of a reader. Yarol, on the other hand, makes good use of his classical education.

Madness Takes Its Toll: In Lovecraft, when a recognizable mental condition shows up, anxiety disorder’s the way to bet. Northwest isn’t so prone—the danger here is addiction.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

There’s nothing like a C.L. Moore story to make me really appreciate the degree to which Lovecraft is not obsessed with sex. Sure, you can read a dozen of his stories without encountering a speaking female character. On the other hand, while women make him pretty nervous, the misogyny mostly stays at a dull roar. Marceline may be a vain seductress—but aside from her, the nastiest fatales are bad-trip Lilith in “Red Hook,” and actually-male Asenath Waite.

On this topic, Lovecraft was not a man of his time. Moore’s first outing dives headfirst into the miasma of pulp gender tropes. Shambleau’s literally a femme fatale, a vampire evolved to mimic a beautiful humanoid woman, who projects compulsion strong enough to distract even someone not prone to “weakness of the flesh.” Her species only mimics the female form. Sorry, straight ladies, you’re just not that tasty.

There’s something very limited about cosmic horror that encompasses human ideas of gender and beauty. Save for Nyarlathotep, few of Lovecraft’s unearthly creatures take much note of the human form except as convenient masquerade outfit (the Yith) or bug on the windshield (Azathoth). Gender, let alone sex, rarely pings the cosmic radar.

What Moore has, in spades, is Page Turning Quality. I may scoff at the pulpy language, and roll my eyes at the gender stuff, but by Pharol I will keep going to find out what happens next! I downloaded a best-of collection to read “Shambleau” on the train, so when I turn the page at the end of a Moore story, I get another Moore story. Speaking of addictive monsters. Most include unholy, incomprehensible eldritch horrors. Most of the incomprehensible eldritch horrors care about human sex appeal—particularly irresistible female beauty. Even Jirel of Joiry, on her first outing, kills with an elder-god-provided kiss. There’s a weird essentialism, up to and including the claim that human feminine beauty is an elemental force of the universe. (A tasty one, of course.) I don’t know enough of Moore to speculate whether this represents some personal conviction, or just a targeted appeal to her readers’ most prurient anxieties.

Still, it’s always fun to watch the pulp adventurer grappling with ancient and incomprehensible forces. Northwest is a jerk, but a fun jerk, and I want to know more about his baby-faced partner. I suspect if I checked any big fanfic site, I’d learn more about both of them. They do have a Han-and-Chewy dynamic, and they spend long days alone together on that spaceship… presumably life isn’t all instinctively repulsive monsters from before the dawn of history.

Speaking of the dawn of history, I love that frame. Man has conquered space before. You may be sure of that. Sort of an inverse Ancient Astronauts. This sort of thing annoys me, intellectually, because it so underestimates the power of human imagination… and yet, it appeals and compels. Fallen and forgotten golden ages are a trope for a reason. And I’m tickled by the idea that some Pliny-ish reports of monsters are inaccurate descriptions of rhinoceroses… and some are inaccurate descriptions of alien monsters from beyond knowable space-time. The latter is really more forgivable, if you think about it.

One last note—I had a whole bit of interpretation, based on Northwest whistling “Green Hills of Earth,” about how “Shambleau” shows what happens when a Heinlein hero finds himself in a Lovecraftian universe. But I was mistaken in seeing deliberate homage. Heinlein’s story and lyrics came 14 years later, in 1947—he got the title from Moore. Which makes you wonder what powers lurk in the background of Heinlein’s space opera, utterly incompatible with the veneer of human hyper-competence.

Anne’s Commentary

Three years out from his “Medusa” collaboration with Zealia Bishop, Lovecraft came across another “Medusa” story by an author making her first professional bow in Weird Tales; he considered “Shambleau” a “magnificent” debut. And so it was! I mean, tentacle-porn starring Han Solo’s great-grandfather on a fantasy Mars? Those make for some tasty fictive elements, although not necessarily in the hands of a young chef.

Moore, however, pulls off a fine mixed grill of classic space opera, erotica, and cosmic terror. We even get an ominous prologue in the high Lovecraftian if-mankind-only-knew-the-truth vein. It presents a notion that must have appealed to Lovecraft, being a version of his own core premise that Earth saw many civilizations before modern humans took over the tricky endeavor. Moore keeps things more local and anthropocentric: the action is confined to our solar system and the previous civilizations were not alien but human. She does hint at alien incursions, however. Did the first human spacefarers find the Shambleau on some outlying planet, bringing back tales that would echo to the ancient Greeks as mythical gorgons? Or did they tempt Shambleaus into following them home? Shambleaus seem peripatetic, appearing on various planets including Mars and Venus, but possibly native to no planet we know. For they come from a “country” far away and long ago. Who knows, maybe in the neighborhood of Empire, First Order and Republic/Rebel Alliances!

Yarol speculates that the Shambleaus may be master illusionists, an idea I like. It makes sense that they would mimic a potential victim’s own species and, um, preferred sexual partner, hence setting their traps with the most attractive baits. They themselves might be just those awful masses of wormy tentacles and slime. That’s reminiscent of the space vampire Robert Bloch imagines in “The Shambler from the Stars,” though the shambler’s a much less subtle hunter. Yarol also wonders whether Shambleau actually have superhuman intelligence, or whether their hypnosis isn’t just an animal adaptation for securing prey. I have to disagree with the Venusian there. What Smith has to tell of his days-long psychic link to the Shambleau, how it shared its memories and thoughts with him, that indicates high intelligence. More: it suggests that the Shambleau-“beloved” relationship is more than a simple predator-prey one. It is at the least a highly complex predator-prey relationship, with the sustenance sought not physical, not even merely mental, but spiritual. The soul, we’re repeatedly told, is the Shambleau’s object, the linking of soul to soul its “language.”

I guess what I’m trying to say is, hell, I like these Shambleaus. From the first time I read the story, I was pissed at Yarol for breaking up Smith’s tryst. Dude was having the time of his life, psychically traveling the cosmos, kind of like a Yuggothian canned brain or Yithian transfer student. [RE: Or a shining Trapezohedron. Speaking of “Shambler”.] Not to mention the never-ending orgasm. Okay, so I mentioned it.

And having mentioned it, I must wonder if Howard blushed reading this tale. What we’ve got here is some in-your-face sexuality, complete with “stirring excitements” and paragraph-long clinches and “soft caressive pressures,” “root-deep ecstasy” and velvet curves and “blind abysses of submission.” Whoa. And isn’t there something both phallic and vaginal in those thick wormy expanding appendages with their grasping moist embrace? Plus it’s happening RIGHT ON PAGE. RIGHT IN FRONT OF US. None of this drawing the curtains on what happened during Edward and Asenath’s honeymoon in beautiful Innsmouth, or exactly what sort of orgies those naughty boys of “The Hound” practiced, or whether Marceline’s hair always behaved itself when she and Denis, you know. Sex. Scary sex. Deadly sex. Days-long sex. And some people depraved enough to get addicted to it, to do it over and over again, ew, ultimate gross-out, right?

Unless, as I wonder, there’s the opportunity for symbiosis in a person-Shambleau relationship. A cool thing about this story is that nobody seems to know much about the species. Yeah, Yarol dumps major info towards the close, but he admits he’s speculating. What’s so bad about soul-to-soul connection, after all? Isn’t it aspirational? Okay, so one soul-mate munching down on the other’s soul, that couldn’t be good. Unless they only have a nibble now and then, keeping their “beloved” alive to share ecstatic psychic journeys.

Or am I imposing New Agey values on the SFF Golden Age?

As usual, many more alleys to explore than time to explore them in. Apart from the Yarol info-dump, I find much to admire in “Shambleau.” The descriptions are vivid, the dialogue space-opera snappy, and the ending intriguingly ambiguous. A major omission there—which Lovecraft would have supplied, at least fleetingly—is the corpse of the monster. Yarol and Smith wake out of their faints to have a nice long discussion of the Shambleau, but where’s the Shambleau gone? Did it dematerialize? Evaporate? Leave not even a stain on the floorboards? Or is there a heap of scorched entrails underfoot while our friends chat? I don’t know. Maybe Smith’s lodging house has really good maid service?

But back to the ambiguity. The monster’s dead, and good thing, too. Or is it dead? Is its death a good thing? Smith’s not so sure. He wonders whether there might not be more Shambleaus to be found. He hesitates to promise he’ll kill a Shambleau on recognition next time. When he does promise, it’s weakly. He won’t do, he’ll try. And his voice wavers.

His voice wavers. That’s a great last line, for it sidesteps the tiresome trope of Hero Recovering from Major Trauma Instantly, and it leaves the reader wondering.

Next week, we skip ahead to the relatively modern—and relatively meta—“Black Man With a Horn” by T.E.D. Klein. It’s anthologized in several collections, but it looks like Cthulhu 2000 and The Book of Cthulhu are your best bets for an e-book.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint in Spring 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

Northwest had an interesting shtick: he never met a beautiful woman he wasn’t willing to sacrifice to keep himself alive. Despite this, he kept running into women who thought it was a good idea to appeal to Smith for help.

The one woman who was completely immune to his charms was Moore’s other big pulp hero, Jirel of Jiory. Jirel had fed better men than Northwest to demons and she wasn’t interested in his useless charms.

Just about every Northwest Smith story is about sex in some way. Some are more obvious than others, but it’s almost always there. The man makes Jim Kirk look like a monk and it almost always comes close to getting him killed. He’d be dead several times over if it weren’t for Yarol.

If there isn’t a fair amount of Smith/Yarol slash out there, then it’s because Moore is less well known among those who write such things. But damn the woman could write. This was her first story, seemingly her first attempt at a story, and it started out as a typing exercise. IIRC, she was typing “The red knight slides down the poker. He balances very badly.” over and over, when the red knight sliding turned into a red figure running.

It’s probably worth noting that Moore was an occasional correspondent with HPL and he was responsible for she and Henry Kuttner meeting.

It’s never stated anywhere specifically, but I have the feeling that Northwest (which these days constantly reminds me of the Kanye/Kardashian spawn) was a nickname based on his initials. Maybe because Yarol often calls him NW. Perhaps his birth certificate reads Norbert Wilson or something similar.

A fine prozine debut from one of the most significant SF writers of her generation.

Weird Tales: “Shambleau” was in November 1933, with Clark Ashton Smith’s “The Holiness of Azedarac” and a reprint of Poe’s “The Premature Burial”.

Lovecraft on Moore: from the blurbs on my Planet Stories edition:

“These tales have a peculiar quality of cosmic weirdness, hard to define but easy to recognize, which marks them out as really unique… In these tales there is an indefinable atmosphere of vague outsideness and cosmic dread which marks weird work of the best sort. The distinctive thing about Miss Moore is her ability to devise conditions and sights and phenomena of utter strangeness and originality, and to describe them in a language conveying something of their outre, phantasmagoric, and dread-filled quality.”

I recall that was Lovecraft was less enthusiastic about some of the sequels, including “Nymph of Darkness” (which was co-authored with Forrest J. Ackerman).

Moore was introduced to Lovecraft by R. H. Barlow: Lovecraft in turn was responsible for Moore’s first meeting with Henry Kuttner. She collaborated with Lovecraft once, writing the opening section of “The Challenge from Beyond”.

Moore on Moore: pulp writers weren’t generally inclined to autobiography (alright, Wonder’s Child) but Moore wrote about the origins of “Shambleau” in the author’s note to The Best of C. L. Moore. She had just accepted a job in a large bank but was an “adequate” rather than professional typist, who practised extensively in her spare time. Halfway down a page, a remembered line of poetry about a red, running figure came to mind, which became the Shambleau of the story. (Moore wasn’t sure which poem this was: she recalled that the figure was a witch fleeing medieval soldiers and that it may have been by William Morris.)

Moore liked to be able to use the unconscious in writing (“This is among life’s most luxurious moments-giving the story its head and just keep your fingers moving.”). This time, her unconscious introduced Northwest Smith, brought in as a way of “giv[ing] the story a shape”: Yarol was then necessary to extricate Smith. She sent the story to Weird Tales, as it was the only fantasy magazine she knew well, and received $100.00 for it.

Later tales: she followed “Shambleau” with “Black God’s Kiss”, which introduced her other recurring character Jirel of Joiry and continued to produce stories in those series throughout the 30’s. In the 1940’s, she collaborated extensively with with her husband Henry Kuttner and continued to produce fine solo efforts such as “Clash By Night”, “No Woman Born” and “Vintage Season”. She retired from writing prose fiction after Kuttner’s death in 1958.

An audio version: read by the author.

@1: “Quest of the Starstone”!

@2: I recall that Northwest Smith’s name came from a man named N. W. Smith, who Moore had had to type a letter to. Yarol is an anagram of her Royal brand typewriter.

I found this one in a collection that also included “Ubbo-Sathla”, so it was a real bargain.

For me, as a budding asexual, the takeaway was “Just say no to drugs.” I had already resolved to do so, and so was freed to wonder what Cytherean frog-broth might taste like. Or whether fluorescent colors were so new in ’33 that they would seem startling to the average so and so even on a strange world.

It wasn’t for many years that I ran onto the rest of the NW Smith stories, which I liked for the atmosphere/setting/details [as with Brackett], bored with the stream of femmes more or less fatale who so often became fatalities. Even the heroic Vaudir, in that story set on Venus–naturally I don’t have the book at hand now–if you evolve too fast, you can’t count on it to stick–anyway, such details as a “tree of life” artistic motif spanning several civilizations, seem to be on more solid ground. And the general euhemeristic idea that monsters and so on are garbled memories of who knows what.

Lastly, it seems tech here might be close to catching up with Smith’s self-heating can of stew, although I don’t recall the exact details; maybe someone can fill me in.

Jirel’s trip to the underworld, as well as “Ubbo-Sathla”, could benefit from a discussion here.

@@.-@: Military style MREs have a “flameless ration heater” which generates heat in an exothermic reaction when water is added to a pad made of iron, magnesium and sodium: http://www.mreinfo.com/mres/flameless-ration-heater/ (this page has my new favourite caption). Self-heating cans work on similar principles: http://heatgenie.com/our-technology/self-heating-technology/how-it-works/.

ETA: Might the anthology you mentioned be Donald A. Wollheim’s The 2nd Avon Fantasy Reader?

Yes, that was the one. I found the 1st volume later one and it had the Venus/Minga/black slime story.

In my limited experience, pulp sci-fi appears to offer straight ladies relatively little in the way of monster sexytimes. (I’m a bi lady)

A very interesting re-take on Shambleau (New Agey values included) comes from the “Central Station” stories by Lavie Tidhar, in particular “Strigoi” (Interzone #242), “The Bookseller” (Interzone #244) and “The Core” (Interzone #246). He does a good job at giving voice to the Shambleau character, as well as deliberately wrapping her story with the Moore framework (she first encounters her “Smith” rescuer in a similar, angry mob scene) along with other noir/pulp fiction motifs. These stories are coming out in May in a fix-up under the title Central Station from Tachyon.

@6: I don’t think the Avon Fantasy Reader magazine gets the recognition it deserves for giving a lot of the classic pulp stories a second life just around the time when hardcover fantasy collections were becoming viable.

@7: Moore’s Jirel actively tries to avoid sexytimes with a demon-god-thing in “The Dark Land” and succeeds rather better than Smith does here.

@8: Tidhar also has a short series about the gunslinger “Gorel of Goliris”, the first five of which are collected in a volume called Black God’s Kiss.

Jirel is roughly infinitely times better at awesome than Northwest is.

When I was listening to a lot of old time radio show archives, I came across a reference to a Northwest Smith radio or at least audio show. Sadly, that was about all I learned about it: not sure when it aired, or who was behind it.

JamesDavisNichol @@@@@ 1: I was thinking of your review as I wrote this. “This ends badly, but not for Smith.”

DemetriosX @@@@@ 2: That’s cool, I didn’t know the origin story. My headcanon for Northwest’s name is that, during the push of interplanetary colonization, there was a trend of naming kids after famous expeditions and explorers–he’s named for the Northwest Passage. Has a sister named Humboldt who does civil engineering on the moon and tries not to think too hard about her nogoodnik brother.

SchuylerH @@@@@ 3: OMG, how did I forget that Moore wrote “Vintage Season”? Her writing got hella better with practice.

AeronaGreenjoy @@@@@ 7: Really an unforgivable oversight. Not much out there for bi ladies, either, unless you really like watching straight boys having fun… or having ambiguously problematic fun, in Northwest’s case.

I had the origin story a little off. It was the white knight sliding down the poker and then she thought of the red figure.

She tells the story here. Schuyler and I sort of had the whole story, but better to read it from the woman herself.

@11: When was the radio series which made reference to the Northwest Smith series broadcast? My usual and unusual sources aren’t finding anything much. As a consolation prize, please accept this French translation of “Shambleau” illustrated by Jean-Claude Forest.

Of course, some of our rereaders may prefer manga: so here’s some Leiji Matsumoto illustrations of Smith and Jirel:

ETA: @12: I wonder whether Humboldt would know about the events of “Lost Paradise”? It’s probably better if she doesn’t…

Northwest possibly being a person of color adds an interesting angle to the brief scene in one of the story collections where Northwest has briefly returned to what’s apparently his home territory. If I remember correctly, it’s somewhere in the south and there’s a ruined plantation house nearby. Although it’s not clear what happened, Northwest would still be in a lot of trouble with the law if they knew he’d come back. That becomes a lot more interesting if you think of it as more the south of the 30’s and Northwest as black or mixed race.

Maybe. On the other hand, his own collaboration about necrophiliac serial killer is also quite a sensual story…

@15: “Now he was not Northwest Smith, scarred outlaw of the spaceways. Now he was a boy again with all his life before him. There would be a white-columned house just over the hill, with shaded porches and white curtains blowing in the breeze and the sound of sweet, familiar voices indoors. There would be a girl with hair like poured honey hesitating just inside the door, lifting her eyes to him. Tears in the eyes. He lay very still, remembering.

Curious how vividly it all came back, though the house had been ashes for nearly twenty years, and the girl—the girl …” – “Song in a Minor Key”

@16: The Eddy stories will prove a challenge for this re-read: as I understood it, the Eddy family do not approve of C. M.’s fiction (especially the collaborative version of “The Loved Dead”) and have used the allegedly still-extant copyright to get his stories taken down from the internet. (There are still a few up but it’s probably better not to let the Eddy family know that.)

@17,thanks! It’s been a while since I read it. “Obedience was not in him” becomes a much more interesting summary if I think of NW as mixed race (we’re told he has light eyes, so mixed race seems more likely) from the south. The story changes to one of interracial romance with the daughter of the angry, violent man whose death he doesn’t regret. Howard would need smelling salts.

It also makes sense with his name. Northwest as an alias for a man from the Southeast.

I never learned anything about the audio production except that it once existed. Maybe.

@19: Have you asked the Old Time Radio Researchers Group about it?